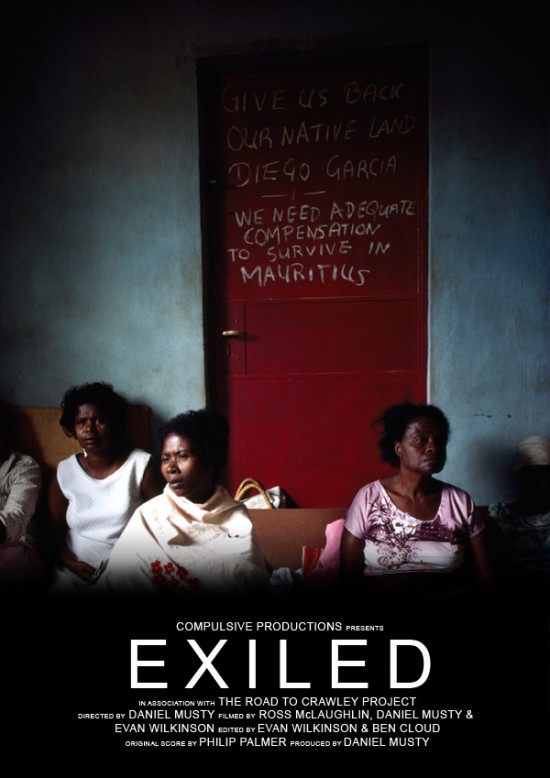

In my last post I discussed the making of the documentary Exiled in 2010 and my experiences of producing a political film during an election year. Whilst reflecting on the film I caught up with President Allen Vincatassin about what life has been like for the UK based Diego Garcians since the making of the film, and the latest developments in their campaign for a return to their island.

In February of 2013 Allen met with Mark Simmonds (then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Foreign Affairs) who agreed to a new feasibility study into the possibility of resettlement in the Chagos including Diego Garcia. The study has now been published and can be found here.

As part of his research, Mark Simmonds visited the island in March 2014 despite protest from Mauritius who are still pursuing claims of sovereignty. He was the first UK minister in history to visit the islands.

The study had favourable results, concluding that there is no legal barrier to resettlement and theorising various options by which a return could be implemented. This feels like a big step forward for the Diego Garcians who have been held back by such feasibility studies in the past. Previous studies have focused on a lack of infrastructure and environmental changes such as rising sea levels, claiming that the island would be uninhabitable despite the contradictory presence of some 5000 military personnel.

The new report in fact states that the ideal island for resettlement within the Chagos Archipelago, is Diego Garcia. The report concedes that the island base means that an infrastructure is in place as Diego Garcia already has a port and airport. Diego Garcia would be better for resettlement than the outer islands because of this existing infrastructure so the presence of the military base has actually become a positive factor in the case for resettlement.

A larger question remains as to how to create jobs and industry on the island and this is one of the areas that now needs research. A number of contractors from the Phillipines currently work at the base, so it is clear that the base does provide potential employment for civilians. Allen has managed to convince the UK government that the defense of the base isn’t a problem as islanders can occupy the other side of the island which is currently uninhabited. In the past, resettlement of Diego Garcia has been discouraged on the basis of it being a threat to international security, but people live next to and near to military bases all over the world.

The US is leasing the land from the UK and the lease officially expires in 2016. The lease will need to be renegotiated soon and the US is in an awkward position following revelations of the island base’s use in renditions flights and as a suspected black prison site – activity which may well be a factor in the USA’s reluctance to have a civilian population nearby. The US are unwilling to allow a civilian population to use any of their infrastructure such as housing, but they have not spoken against civilian use of the port and airport where immigration is controlled by the UK.

A week before Parliament’s dissolution, James Dudderidge, Simmonds’ successor at the Foreign Office, said that there is more work to be done to make a decision as to how resettlement could happen and who would want to return.

Allen has said that there is a need for more in depth work to be done as to who would like to return to the islands but the very realistic terms in which resettlement is now being discussed are encouraging. People have begun to register their interest in returning.

Allen has been in discussions with the Foreign Office about a pilot resettlement. One of the big questions is how much the resettlement will cost the treasury.

My conversation with Allen was conducted before the general election, this progress was made with the coalition government and the hope is that the work can continue when the new government come to power. There is a need for more studies in order to work towards a pilot resettlement in order to see if permanent resettlement could be sustainable. The Diego Garcians have a plan and are waiting to present it to the new government.

Today marks the State Opening of Parliament and with James Dudderidge and the Foreign Minister Philip Hammond returning to their posts it is hopeful that these discussions will continue to progress.

Looking back on the film.

Allen’s reflection on the documentary is that it highlighted the Diego Garcian’s story very well but he can’t confirm what impact it had on the local or national public. The biggest hope was that the film would reach a wider audience than just the local screenings that it was commissioned for and the Diego Garcian society haven’t had the resources to organize further screenings of the film. It seems that the Road to Crawley project hasn’t continued much contact with the community since the film was made.

Henry is still Crawley’s MP and Laura has retired from politics but both have continued their support for the cause. Henry has helped a lot with organizing meetings with Mark Simmonds to negotiate resettlement and speaking on the Diego Garcians’ behalf in Parliament on several occasions. Allen’s feeling before the election was that if the Conservatives remain in government then the DG population stand a good chance of achieving their right to return home.

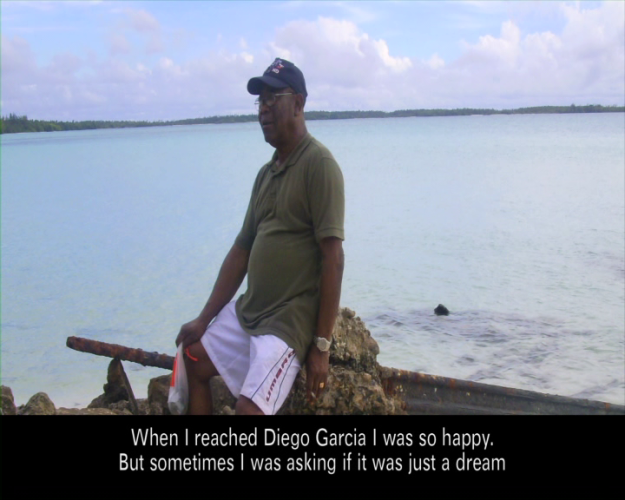

Charlesia (Saji) Alexis sadly passed away in December 2012.

Myleene continues her work with the Sega dancers and the Diego Garcian youth group.

Marie-Ange has made progress learning English and is now living in the Brighton area.

Selmour is well and enjoying being a Grandfather.

Allen has self-published his memoir Flight to Freedom which is now available on Amazon.

About the Author:

Evan Wilkinson is a Community Filmmaker based in Brighton. As well as producing videos and community film projects, Evan teaches workshops in filmmaking, script development and animation. For more information please visit: http://evanwilkinson.co.uk